A Fading Legacy: The Nath Story

Times of Bennett | Updated: Oct 11, 2025 11:50

Correspondent: Sampada Sharma

Along the parched lanes of rural India, where tradition and survival entwine, the echo of aflute once drew crowds to a spectacle both mesmerizing and mysterious: snake charming, a craft immortalized by the Nath community for centuries. Their lives, music, and knowledge have threaded through India’s collective memory, yet now this ancient tribe faces a struggle for recognition and for survival.

Roots in Myth and Reverence

The Nath snake charmers, also known as saperas, hail from a lineage steeped in legend. Their founding myth, passed down orally for generations, tells ofGuru Gorakhnath and his disciple Kanipa, who were blessed with the ability to handle venom and protect serpents making the Nath tribe guardians of mystical lore. Snake charming was never just entertainment; it was deeply spiritual. For the Naths , the serpent is sacred, echoing through Hindu mythology in the coils that wrap Shiva’s neck and undulate beneath Vishnu’s throne.

But what sets the Naths apart is the bond they share with the snakes. When they capture snakes for their craft, they bring them from Assam a place rich in serpent lore. Tradition says they make a promise to the snakes: after a certain period, they will return them back to their origins. It is a gesture of respect and responsibility, demonstrating a relationship built not only upon livelihood but also trust.

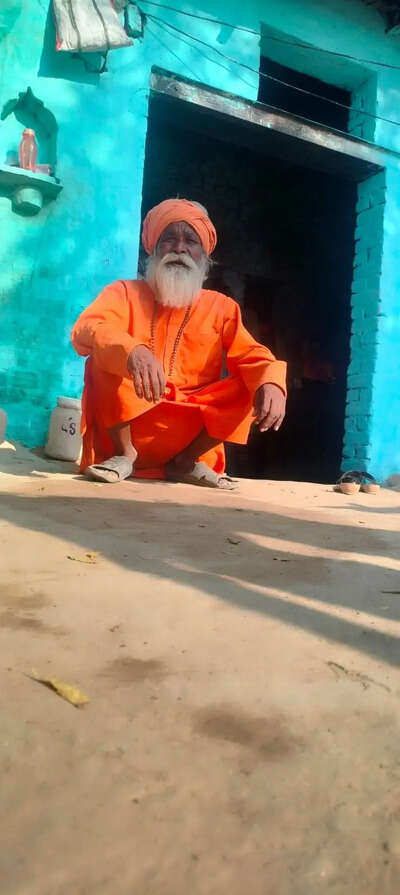

“सााँप हमारे रोज़ी-रोटी है” (“Snakes are our livelihood”), saysBallo Nath , his weathered hands clutching the bamboo flute, or been. The bamboo box and cloth, once the heart of village festivities, are now potent reminders of a lost era.

Tradition Meets Law: The Quieting of the Flute

In 1991, the Indian government enforced a ban on snake charming with theWildlife Protection Act (1972, amended 2003). The law was rooted in concern for endangered species and animal welfare, but for thousands of Naths, it struck at their identity and primary means of subsistence. According to Sahapedia, settlements like the Sapera Basti in Delhi, now home to 4,500 saperas, are emblematic of communities forced to the margins by changing policy and urbanization.

The effect has been profound. Where the been once dictated rhythm and spectacle, most Nath families now earn barely Rs 10,000 - 15,000 monthly, supporting six-member households and battling new pressures like early marriage and substance abuse. Some adapted to manual labor; others turned to catching snakes that wander into homes, their expertise barely offset by meager compensations. Their vast, inherited wisdom on snakes what is venomous, what heals, what harms remains largely ignored by mainstream society.

Struggle and Change: Between Survival and Obsolescence

Despite hardships, fragments of tradition persist. In some Nath families, snake venom is blended into eye kohl, or kajal, in the belief that it cures sight a mystical practice passed down for generations. However, there is no scientific proof that snake venom has any benefits for eyesight, and medical experts do not recommend the practice. Ceremonies likeNaag Panchami bring occasional demand, but the art is mostly fading. The next generation is looking to schools and new hopes, their instruments and yellow dhotis worn only on rare, ceremonial days.

Yet the unresolved question remains: Should the government have reformed their methods rather than extinguish their age-old vocation? Experts and community leaders believe a controlled, respectful revival could balance conservation with cultural sustenance. In recent years, rehabilitation efforts have turned charmers into snake rescuers teaching communities how serpents support local ecosystems and offering the saperas a chance to pass down their heritage as environmental stewards.

The World That Ought to Know

“To the world, we are invisible,” mourns an elder Nath. Behind the headlines about wildlife protection and obsolete trades lies a question of dignity, belonging, and the importance of preserving not just species, but stories. The Nath tribe deserves recognition for its unique expertise for the centuries-old symbiosis with one of nature’s most feared and revered creatures.

As India modernizes, sweeping aside traditions in the name of progress, the sound of the been grows faint. The story of the Naths urges us to imagine not just lost performances, but a world richer with wisdom, music, and the struggle of a community to keep its legacy alive.

(The writer is a second-year student of BA Mass Communication. She is passionate about Expression and Media. And loves to write in her free time)

Along the parched lanes of rural India, where tradition and survival entwine, the echo of a

Roots in Myth and Reverence

The Nath snake charmers, also known as saperas, hail from a lineage steeped in legend. Their founding myth, passed down orally for generations, tells of

But what sets the Naths apart is the bond they share with the snakes. When they capture snakes for their craft, they bring them from Assam a place rich in serpent lore. Tradition says they make a promise to the snakes: after a certain period, they will return them back to their origins. It is a gesture of respect and responsibility, demonstrating a relationship built not only upon livelihood but also trust.

“सााँप हमारे रोज़ी-रोटी है” (“Snakes are our livelihood”), says

Tradition Meets Law: The Quieting of the Flute

In 1991, the Indian government enforced a ban on snake charming with the

The effect has been profound. Where the been once dictated rhythm and spectacle, most Nath families now earn barely Rs 10,000 - 15,000 monthly, supporting six-member households and battling new pressures like early marriage and substance abuse. Some adapted to manual labor; others turned to catching snakes that wander into homes, their expertise barely offset by meager compensations. Their vast, inherited wisdom on snakes what is venomous, what heals, what harms remains largely ignored by mainstream society.

Struggle and Change: Between Survival and Obsolescence

Despite hardships, fragments of tradition persist. In some Nath families, snake venom is blended into eye kohl, or kajal, in the belief that it cures sight a mystical practice passed down for generations. However, there is no scientific proof that snake venom has any benefits for eyesight, and medical experts do not recommend the practice. Ceremonies like

Yet the unresolved question remains: Should the government have reformed their methods rather than extinguish their age-old vocation? Experts and community leaders believe a controlled, respectful revival could balance conservation with cultural sustenance. In recent years, rehabilitation efforts have turned charmers into snake rescuers teaching communities how serpents support local ecosystems and offering the saperas a chance to pass down their heritage as environmental stewards.

The World That Ought to Know

“To the world, we are invisible,” mourns an elder Nath. Behind the headlines about wildlife protection and obsolete trades lies a question of dignity, belonging, and the importance of preserving not just species, but stories. The Nath tribe deserves recognition for its unique expertise for the centuries-old symbiosis with one of nature’s most feared and revered creatures.

As India modernizes, sweeping aside traditions in the name of progress, the sound of the been grows faint. The story of the Naths urges us to imagine not just lost performances, but a world richer with wisdom, music, and the struggle of a community to keep its legacy alive.

(The writer is a second-year student of BA Mass Communication. She is passionate about Expression and Media. And loves to write in her free time)