Bojack Horseman And The Myth Of Good Damage

Times of Bennett | Updated: Nov 18, 2025 16:49

Correspondent: Ananya Barath

“Because if I don’t (write the memoir) that means all the damage I got isn’t good damage, it’s just damage. I have gotten nothing out of it and all those years I was miserable was for nothing. I could’ve been happy this whole time…”

It should be entirely surprising that a show about an anthropomorphic horse’s struggle for normalcy was the match that sparked a philosophical conundrum - "is pain a requisite for ‘good’ art?" But if you’ve even so much as heard ofBoJack Horseman , you’d know that’s only the beginning of the panoply of questions that the show attempts to unravel.

Spanning six seasons and a total run time of seven hours and forty minutes, the show is a masterclass on the classic switch and bait, lulling its viewers into a false sense of serenity with its oversaturated colour palette and whimsical cartoon-like style in its initial stages.

The characters appear to be carbon copies of unoriginal stereotypical sitcom tropes: the lovable doofus serving as comic relief, the too-intelligent-for-her-own-good best friend, the protagonist who emerges victorious every time, despite the bad cards they’ve been dealt by life.

But throughout the course of the show the writers shatter the fragile facade of perfection they’ve built around these characters revealing their gritty and helpless nature underneath, forcing the viewers to stop taking things at face value.

In its 70th episode, titled ‘Good Damage’, the show explores the idea of becoming better as a result of the trauma its characters have experienced. The episode is centred around series regular,Diane Nguyen , who struggles to write her memoir, finding it difficult to articulate the ineffable pain she endured throughout her childhood.

What’s odd is that in the process of failing to write a thought-provoking autobiography dealing with heavy themes, she accidentally ends up writing an upbeat young adult fiction about Ivy Tran, a Vietnamese-American teenage detective who solves mysteries in the mall.

Instead of embracing this unexpected creative shift, she rejects the idea,dismissing it as too silly and derivative. Her scepticism is mostly spearheaded by the self-imposed pressure to transform her endured pain into something inspiring and profound.

WhileDiane ’s thought process might seem foreign to some, it’s certainly not an uncommon one.

The Japanese in particular were fond of this concept coining the philosophy of kintsugi, an embracing of the flawed or imperfect. The theory behind it was to highlight cracks and repairs as events in the life of an object, rather than allowing its service to end at the time of its damage or breakage.

This ideology, however, later shifted drastically, as collectors became so enamoured of the new art that some were accused of deliberately smashing valuable pottery so it could be repaired with the gold seams ofkintsugi . Pottery pieces were also chosen for deformities it had acquired during production, then deliberately broken and repaired, instead of being trashed.

Van Gogh is also often viewed as the supposed pioneer for this concept. There’s a myth that his artworks are as good as they are only because of the manic depression he endured all through his life; his creativity festering in ways that wouldn’t have been possible if it wasn’t for this unusual catalyst.

So, people induced this pain deliberately on the off chance that it would result in them being the next Van Gogh to walk the earth. Pain is what makes good artists great…or at least that’s the idea being reinforced constantly. The truth, of course , is far more complicated.

Diane refers to the concept of Kintsugi multiple times during the course of the show, most notably during her divorce from Mr.Peanutbutter . She uses it as a guiding philosophy in an attempt to make sense of her pain by framing it as beautiful and necessary.

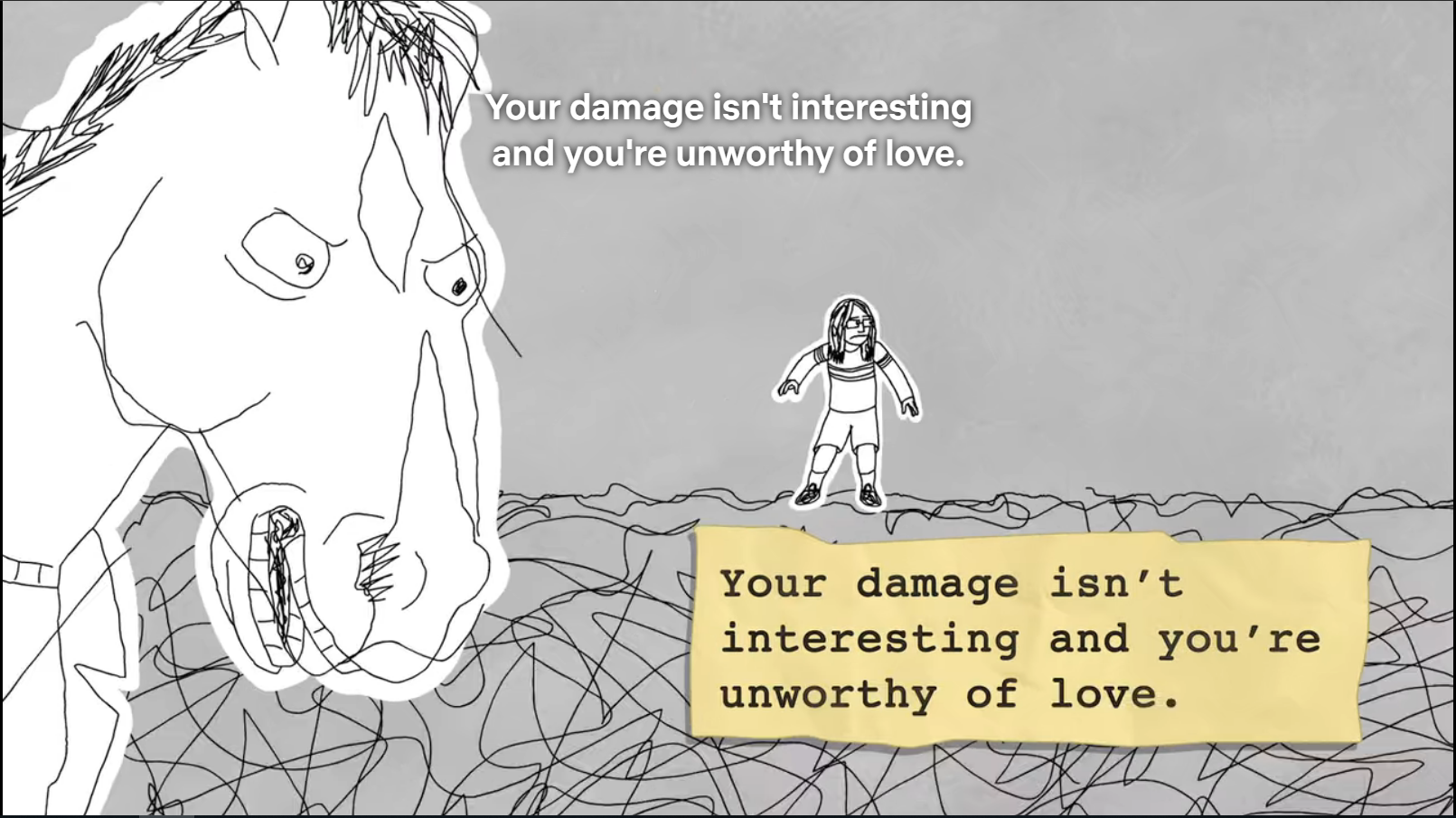

Visually, the episode does a brilliant job by drawing a stark contrast between the stories she wants to tell and the one her mind explores instead. When Diane tries to recount her own trauma, the animation becomes sketchy, jagged, chaotic and barely formed as though the memories themselves are resisting clarity.

But when she writes about the ‘silly’ teenage detective, the visuals shift dramatically. The graphics are fluid, vibrant and full of colour – each scene full of ease and flowing with confidence.

It becomes painfully clear that Diane is clinging to her pain, repeating the philosophy of kintsugi like a mantra, desperate to believe that all her suffering must hold significance. But all she’s left with is a tangled mess of memory and expectation.

We, as humans, are conditioned to believe that experiencing agony and misery makes us better somehow. We’re expected to view each obstacle as the beginning of an inevitable success story. Every autobiography always must follow the same formula; a rags to riches tale about someone who’s beenbetrayed by life seemingly at every point.

But at the end of the one-and-a-half-hour mark, all the agony the protagonist endured is justified – redeemed by the laurels they now get to rest on and the closure they’ve supposedly found along the way.

It leads people to believe that unless they’ve endured something tragic, they’ll never achieve anything meaningful or that any pain they do experience must be transformed into something Oscar worthy.

“If I could have worked without this accursed disease, what things I might have done,” Van Gogh wrote in one of his last letters to his younger brother.

“Good Damage” ends with Diane completing her book about a teenage detective, symbolising her willingness to let her pain exist as it is, no longer burdened by the urge to “make it count”.

The episode is a stark reminder of the simple truth that sometimes, damage is just damage and there is no need to repurpose it to keep living.

Ananya Barath is a second year BA Mass Communication student who is fueled by an obsession with stories that blend the ancient with the modern (yes, she's the type to speculate whether Iron Man would beat Theseus in battle).

“Because if I don’t (write the memoir) that means all the damage I got isn’t good damage, it’s just damage. I have gotten nothing out of it and all those years I was miserable was for nothing. I could’ve been happy this whole time…”

It should be entirely surprising that a show about an anthropomorphic horse’s struggle for normalcy was the match that sparked a philosophical conundrum - "is pain a requisite for ‘good’ art?" But if you’ve even so much as heard of

Spanning six seasons and a total run time of seven hours and forty minutes, the show is a masterclass on the classic switch and bait, lulling its viewers into a false sense of serenity with its oversaturated colour palette and whimsical cartoon-like style in its initial stages.

The characters appear to be carbon copies of unoriginal stereotypical sitcom tropes: the lovable doofus serving as comic relief, the too-intelligent-for-her-own-good best friend, the protagonist who emerges victorious every time, despite the bad cards they’ve been dealt by life.

But throughout the course of the show the writers shatter the fragile facade of perfection they’ve built around these characters revealing their gritty and helpless nature underneath, forcing the viewers to stop taking things at face value.

In its 70th episode, titled ‘Good Damage’, the show explores the idea of becoming better as a result of the trauma its characters have experienced. The episode is centred around series regular,

What’s odd is that in the process of failing to write a thought-provoking autobiography dealing with heavy themes, she accidentally ends up writing an upbeat young adult fiction about Ivy Tran, a Vietnamese-American teenage detective who solves mysteries in the mall.

Instead of embracing this unexpected creative shift, she rejects the idea,dismissing it as too silly and derivative. Her scepticism is mostly spearheaded by the self-imposed pressure to transform her endured pain into something inspiring and profound.

While

The Japanese in particular were fond of this concept coining the philosophy of kintsugi, an embracing of the flawed or imperfect. The theory behind it was to highlight cracks and repairs as events in the life of an object, rather than allowing its service to end at the time of its damage or breakage.

This ideology, however, later shifted drastically, as collectors became so enamoured of the new art that some were accused of deliberately smashing valuable pottery so it could be repaired with the gold seams of

So, people induced this pain deliberately on the off chance that it would result in them being the next Van Gogh to walk the earth. Pain is what makes good artists great…or at least that’s the idea being reinforced constantly. The truth, of course , is far more complicated.

Diane refers to the concept of Kintsugi multiple times during the course of the show, most notably during her divorce from Mr.

Visually, the episode does a brilliant job by drawing a stark contrast between the stories she wants to tell and the one her mind explores instead. When Diane tries to recount her own trauma, the animation becomes sketchy, jagged, chaotic and barely formed as though the memories themselves are resisting clarity.

But when she writes about the ‘silly’ teenage detective, the visuals shift dramatically. The graphics are fluid, vibrant and full of colour – each scene full of ease and flowing with confidence.

It becomes painfully clear that Diane is clinging to her pain, repeating the philosophy of kintsugi like a mantra, desperate to believe that all her suffering must hold significance. But all she’s left with is a tangled mess of memory and expectation.

We, as humans, are conditioned to believe that experiencing agony and misery makes us better somehow. We’re expected to view each obstacle as the beginning of an inevitable success story. Every autobiography always must follow the same formula; a rags to riches tale about someone who’s beenbetrayed by life seemingly at every point.

But at the end of the one-and-a-half-hour mark, all the agony the protagonist endured is justified – redeemed by the laurels they now get to rest on and the closure they’ve supposedly found along the way.

It leads people to believe that unless they’ve endured something tragic, they’ll never achieve anything meaningful or that any pain they do experience must be transformed into something Oscar worthy.

“If I could have worked without this accursed disease, what things I might have done,” Van Gogh wrote in one of his last letters to his younger brother.

“Good Damage” ends with Diane completing her book about a teenage detective, symbolising her willingness to let her pain exist as it is, no longer burdened by the urge to “make it count”.

The episode is a stark reminder of the simple truth that sometimes, damage is just damage and there is no need to repurpose it to keep living.

Ananya Barath is a second year BA Mass Communication student who is fueled by an obsession with stories that blend the ancient with the modern (yes, she's the type to speculate whether Iron Man would beat Theseus in battle).